This report is the first in a series on the situation of women's sport in Iran to be published by Small Media during the London 2012 Olympics. This piece gives a historical background, describing the status of women's sport in Iran before the 1979 Revolution.

- "Islamic women’s sport appears to be a contradiction in terms - at least this is what many in the West believe. … In this respect the portrayal of the development and the current situation of women’s sports in Iran is illuminating for a variety of reasons. It demonstrates both the opportunities and the limits of women in a country in which Islam and sport are not contradictions" (Pfister 2003: 207)

- As the Olympics approaches, and issues of women athletes from Muslim majority countries are splashed across the headlines, Small Media has embarked on a research of the history, structure and representation of women’s sport in Iran. This subject received much coverage in the wake of the disqualification of the Iranian women’s football team from Olympic qualifying under controversial circumstances. However, while there is a wealth of information about women’s sport in Iran after the revolution, there is a dearth on the pre-revolution period.

To discuss women’s sporting in Iran without taking into consideration its evolution prior to the revolution, is to look at the present state of women’s sports in a vacuum. As the first in a series of reports on Iranian women’s sporting to be published by Small Media during the London 2012 Olympics, this piece describes the status of women’s sporting before the Iranian Revolution (1979), contextualising our upcoming reports, which explore more contemporary issues.

Early Sporting in Iran

Prior to the 1850s, the traditional emphasis on physical fitness and training in Iran was in the context of ‘being fit for war’. The long-held tradition of Iranian wrestling, which was practiced in Zurkhaneh (‘houses of strength’), along with emphases on horse riding and training with clubs, exemplifies this intersection of war and sport (Jahromi 2011; Chehabi 2002).

With the increase in travel and international labour migration in the mid-19th century, and the spread of ideas associated with these population movements, modern sport and physical activities began to develop in Iran. However, it was not until the early 20th century when such ideas started being institutionalised by the state. For example, in 1919 Iran’s schools officially adopted the Swedish gymnastics system developed by Pehr Henrik Ling (Jahromi 2011; Chehabi 2002).

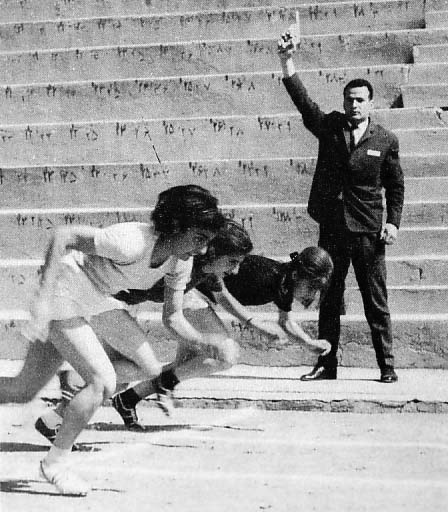

Although such sports were almost exclusively male-only domains, with the coming of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1926, measures were introduced to include physical activities and education for women and girls. Reza Shah was a ‘moderniser’ (like his contemporary Mustafa Kemal Ataturk in Turkey), and saw European-style physical education and sport as integral to his plan. In 1927, compulsory physical education in schools for both boys and girls was approved by the Majles (Parliament) (Chehabi 2002). The Pahlavi Dynasty and Women’s Sport

"Under the Shah’s regime, the sporting agenda was Westernisation and sport, and part of the nationalistic agenda focused on elite performers and international competitions in mixed-sex environments" (Jahromi 2011: 114)

In 1934, Reza Shah declared the mandatory unveiling of women, and in 1935 established the state-sponsored Ladies’ Centre (Kanun-e Banovan), which became one of the main organisations pursuing women’s sport. However, as Leila Mouri and Kristin Soraya Batmanghelichi point out in their forthcoming article “Ex-sporting the Hejab: Reflections on the Discourse of Compulsory Hejab and Iranian Women’s Soccer” (2012; forthcoming),

"These projects were mainly limited to the upper strata of society, and thus far women’s sports had not yet become a national pastime and concern. Still, pictures of Iranian female pilots or parachutists and young women’s and school girls’ sports training practices, appeared in Iranian journals and newspapers en masse"

Although conservatives opposed women’s sport and girls’ physical education, as the wearing of sportswear in public violated the Islamic dress code, women from non-devout upper and middle class backgrounds became increasingly involved in a diverse range of sports (Chehabi 2002). With the abdication of Reza Shah in 1941, his son, Mohammed Reza Shah, assumed the throne and continued his father’s modernisation agenda.